Spegel vs Harbor: Which Pull-Through Cache Should You Choose?

If you’re running Kubernetes clusters and hitting DockerHub rate limits, you need a pull-through image cache, a solution where images pulled by one node are automatically shared with other nodes in the cluster instead of each node pulling them individually from the internet. But which one? In this post, I’ll walk through my decision process comparing Harbor and Spegel for multi-node bare-metal clusters, share real deployment experiences with both solutions, and help you choose the right tool based on your operational constraints.

This post is for: DevOps engineers and platform teams evaluating pull-through cache solutions for Kubernetes clusters with 10+ nodes, particularly those who manage multiple clusters with limited operational capacity.

TL;DR

Problem solved: Eliminated DockerHub rate limit failures during cluster provisioning for two 10-15 node bare-metal Kubernetes clusters behind NAT.

Solution chosen: Spegel (distributed P2P cache) over Harbor (centralized registry platform).

Why Spegel won: Zero operational overhead after initial setup, inherently distributed architecture matching our existing cluster design, and minimal infrastructure dependencies. It reuses containerd’s existing storage without requiring databases, certificates, or persistent volumes.

🔗 Spegel on GitHub | Harbor on GitHub

The Problem: Rate Limits Meet Multi-Node Clusters

I’ve been running two bare-metal Kubernetes clusters for a university project (one for development, one for production) each spanning 10-15 nodes for a while now. I’ve automated the cluster setup with Ansible, and the infrastructure works well, but we have a recurring pain point: DockerHub rate limits.

The problem became acute when provisioning new nodes or spinning up fresh clusters. DockerHub’s anonymous rate limit with 200 pulls per 6 hours per IP sounds reasonable but was not sufficient because:

- All nodes sit behind NAT, appearing as a single IP to DockerHub

- Each node needs to pull dozens of container images on first boot

- Spinning up a 15-node cluster means potentially hundreds of image pulls in minutes

I could authenticate with a DockerHub API key to increase the limit, but that felt like a band-aid: managing credentials across clusters, and still being subject to limits when growing the cluster sizes. So instead, I looked for a different solution.

The specific issues driving this decision:

- DockerHub rate limits: Hitting the anonymous pull limit regularly, blocking cluster provisioning

- Reliability concerns: Depending on DockerHub’s availability for every image pull felt ok for the start, but we wanted more reliability

- Pull performance: Images pulling from the internet for every node was slower than necessary

The Candidates: Two Approaches to Image Distribution

After some research, I narrowed the field to two fundamentally different solutions.

Harbor: The CNCF Graduated Registry Platform

Harbor is a feature-rich container registry platform that happens to support pull-through caching. It’s a CNCF graduated project with features including vulnerability scanning, image signing, replication, RBAC, multi-tenancy, and proxy caching for upstream registries.

My first impression: feature-rich and comprehensive. Harbor packs a lot of capabilities, which raises an immediate question: do I run this inside my clusters or as a shared service outside them? For multiple teams or applications, you might run Harbor as centralized infrastructure. For my use case (two isolated clusters) I could run one per cluster.

Spegel: The Kubernetes-Native P2P Mirror

Spegel is purpose-built for one thing: distributed image mirroring within a Kubernetes cluster. It runs as a DaemonSet, so one pod per node, turning each node into both a consumer and provider of container images. The architecture is stateless and peer-to-peer.

My first impression: lightweight and focused. Spegel does exactly what I needed, nothing more. The deployment model is obvious: it lives in-cluster, period. No architectural decisions to make about topology or multi-cluster sharing.

First impression summary: Harbor is a Swiss Army knife; Spegel is a scalpel.

My Decision Criteria

Every project differs, and so should the tools that are used. In my project, I followed the following decision criteria:

1. Kubernetes-Native Integration

I’m already running Kubernetes with all its operational complexity: three-node control-plane HA setup, monitoring with Prometheus, logging aggregation, and so on. Adding a solution that integrates naturally with this existing infrastructure means I don’t have to context-switch to a separate system.

Kubernetes-native also means using the primitives I already understand: DaemonSets, Services, ConfigMaps. I can reuse my existing monitoring and alerting setup rather than learning a new system’s operational model.

2. Minimal Operational Complexity

I’m a solo operator on this project, so keep it simple is the philosophy. Every additional system I run is something else that can break, need upgrading, require monitoring, or demand my attention.

The ideal solution would have low operational complexity: simple to understand, few moving parts, and graceful degradation if something breaks. The caching layer should be optional infrastructure that makes things better, not critical path that can cause outages.

3. No Single Point of Failure

We’ve invested effort into an automated Kubernetes setup with three control-plane nodes with self-healing capabilities. Caching container images is prone to become a single-point of failure if not done right, so the solution should be fault tolerant. If I’m going to run distributed infrastructure, the caching layer should be distributed too. The architecture should align: distributed container orchestration deserves distributed image distribution.

What I explicitly didn’t prioritize

Harbor comes with many features that, while useful in other contexts, were overkill for my needs:

- Vulnerability scanning and image signing were not compliance requirements for this project

- Multi-tenancy and RBAC for two clusters and one operator? Unnecessary complexity

- Hosting private images was not needed, we’re only pulling public images from upstream registries

I needed a pull-through cache, not a full container registry platform.

Evaluating Harbor

I installed Harbor on our dev cluster via helm to see what running it actually involves.

Architecture

Harbor deploys multiple components:

Core components:

- PostgreSQL database: Stores metadata, user data, access policies

- Redis: Handles caching and job queuing

- Core services: API server, web UI, registry proxy

- Persistent storage: For cached container images

- Optional: Trivy (vulnerability scanning), Notary (image signing)

How pull-through caching works:

- Create a “proxy project” in Harbor pointing to an upstream registry (e.g., DockerHub)

- Configure your cluster nodes to pull images through Harbor instead of directly from upstream

- Harbor intercepts image pulls, fetches from upstream if not cached, stores locally

- Subsequent pulls for the same image are served from Harbor’s cache

This architecture made sense to me, but configuration was tedious.

Operational Reality: Where Things Got Complex

Initial setup (the easy part):

Deploying Harbor via Helm was straightforward: the chart is mature and well-documented. Within minutes, I had Harbor running with its database, Redis, and core services (though not in high-availability setup).

Configuration (the tedious part):

Creating proxy projects requires using the Harbor UI or API. I wanted this automated for reproducibility, so I wrote a post-install Helm hook script using harbor-cli to create the proxy project automatically. Even though it worked in the end, it felt weird that such a fundamental configuration, I had to write the following:

{{- if .Values.proxyProjects }}---apiVersion: v1kind: ConfigMapmetadata: name: {{ .Release.Name }}-setup-script namespace: {{ .Release.Namespace }} annotations: "helm.sh/hook": post-install,post-upgrade "helm.sh/hook-weight": "0" "helm.sh/hook-delete-policy": before-hook-creation,hook-succeeded,hook-faileddata: setup.sh: | #!/bin/sh set -e

HARBOR_URL="{{ .Values.harbor.externalURL }}" HARBOR_USER="admin" HARBOR_PASSWORD="{{ .Values.harbor.harborAdminPassword }}"

# Wait for Harbor to be ready echo "Waiting for Harbor to be ready..." for i in $(seq 1 60); do wget -q -O- "${HARBOR_URL}/api/v2.0/health" >/dev/null 2>&1 && break sleep 5 done echo "✓ Harbor is ready"

# Login to Harbor echo "Logging in to Harbor..." /harbor login "${HARBOR_URL}" -u "${HARBOR_USER}" -p "${HARBOR_PASSWORD}" >/dev/null 2>&1 echo "✓ Logged in to Harbor"

{{- range .Values.proxyProjects }} # Get or create registry: {{ .registryName }} REGISTRIES_JSON=$(/harbor registry list --output-format json 2>/dev/null || echo "[]")

if echo "$REGISTRIES_JSON" | grep -q "{{ .registryName }}"; then echo "Registry '{{ .registryName }}' already exists" REGISTRY_ID=$(wget -q -O- "${HARBOR_URL}/api/v2.0/registries" \ --header="Authorization: Basic $(echo -n "${HARBOR_USER}:${HARBOR_PASSWORD}" | base64)" | \ sed -n 's/.*"id":\([0-9]*\),[^}]*"name":"{{ .registryName }}".*/\1/p' | head -n1) else echo "Creating registry: {{ .registryName }}..." /harbor registry create \ --name "{{ .registryName }}" \ --type "{{ .registryType }}" \ --url "{{ .registryUrl }}" \ --description "{{ .description }}" \ --insecure=false \ {{- if .registryCredential }} --credential-access-key "{{ .registryCredential.accessKey }}" \ --credential-access-secret "{{ .registryCredential.accessSecret }}" \ --credential-type basic \ {{- end }} >/dev/null 2>&1

sleep 2 REGISTRY_ID=$(wget -q -O- "${HARBOR_URL}/api/v2.0/registries" \ --header="Authorization: Basic $(echo -n "${HARBOR_USER}:${HARBOR_PASSWORD}" | base64)" | \ sed -n 's/.*"id":\([0-9]*\),[^}]*"name":"{{ .registryName }}".*/\1/p' | head -n1) echo "✓ Created registry: {{ .registryName }}" fi

[ -z "$REGISTRY_ID" ] && echo "ERROR: Failed to get registry ID for {{ .registryName }}" && exit 1

# Get or create project: {{ .name }} PROJECTS_JSON=$(/harbor project list --output-format json 2>/dev/null || echo "[]")

if echo "$PROJECTS_JSON" | grep -q "{{ .name }}"; then echo "Project '{{ .name }}' already exists" else echo "Creating project: {{ .name }}..." {{- if .public }} /harbor project create "{{ .name }}" --proxy-cache --registry-id "${REGISTRY_ID}" --public --storage-limit=-1 >/dev/null 2>&1 {{- else }} /harbor project create "{{ .name }}" --proxy-cache --registry-id "${REGISTRY_ID}" --storage-limit=-1 >/dev/null 2>&1 {{- end }} echo "✓ Created project: {{ .name }}" fi {{- end }}

echo "✓ Harbor setup complete"---apiVersion: batch/v1kind: Jobmetadata: name: {{ .Release.Name }}-setup namespace: {{ .Release.Namespace }} annotations: "helm.sh/hook": post-install,post-upgrade "helm.sh/hook-weight": "1" "helm.sh/hook-delete-policy": before-hook-creation,hook-succeeded,hook-failed labels: app: {{ .Release.Name }}-setupspec: backoffLimit: 3 template: metadata: labels: app: {{ .Release.Name }}-setup spec: restartPolicy: Never containers: - name: setup image: registry.goharbor.io/harbor-cli/harbor-cli:latest command: ["/bin/sh", "/scripts/setup.sh"] volumeMounts: - name: setup-script mountPath: /scripts env: - name: HARBOR_URL value: "{{ .Values.harbor.externalURL }}" volumes: - name: setup-script configMap: name: {{ .Release.Name }}-setup-script defaultMode: 0755{{- end }}This felt complex for such a basic use case. I looked into the Harbor Operator project, which seemed promising, but it’s abandoned now. The lack of a maintained declarative config option made Harbor feel less Kubernetes-friendly than I expected.

Where I stopped: certificates:

Here’s where Harbor’s architecture clashed with my requirements. Containerd doesn’t allow pulling from HTTP registries, it requires HTTPS (unless configured otherwise, opening up potential attack vectors). That means Harbor needs TLS certificates.

The standard approach is to:

- Expose Harbor externally via an Ingress

- Let something like cert-manager handle TLS certificates (using Let’s Encrypt)

- Configure nodes to trust the certificates

But I wanted to keep Harbor cluster-internal to reduce the attack surface. Why expose a caching layer to the internet? This meant

- Manually managing internal CA certificates

- Distributing CA certificates to all cluster nodes

- Configuring containerd on each node to trust the internal CA

- Handling certificate rotation

The complexity kept growing. For a caching layer that’s supposed to make things easier, this was too much complexity.

High availability implications:

Running Harbor properly would need:

- PostgreSQL in HA mode (replication, failover)

- Redis in HA mode (Sentinel or Cluster)

- Multiple Harbor core service replicas

- Shared persistent storage or replicated storage

While doable (we already run cnpg Postgres clusters and Longhorn for replicated volumes), each component adds operational burden. I’d be running a distributed database cluster, a Redis cluster, and coordinating stateful services just to cache some images. It felt overkill.

How Harbor Matched My Criteria

Kubernetes-Native Integration:

Harbor runs on Kubernetes but doesn’t feel native to it. It’s a traditional stateful app ported to K8s. You manage databases, configure external services, and work around mismatches between Harbor’s design and Kubernetes patterns (like having to script proxy project creation).

There’s a Harbor operator, but it’s abandoned. I hope that’ll change in the future and a successor will make the adoption in kubernetes easier.

Operational Complexity:

- Database backups: PostgreSQL needs backup strategy

- Multiple stateful components: Redis, PostgreSQL, image storage all need care

- Certificate management: Either expose externally or manage internal CA infrastructure

- Monitoring: Need to monitor database health, Redis, storage capacity, Harbor services

- Configuration drift: Proxy projects and settings live in the database, not declarative config

For me, this felt overkill for what I needed.

Single Point of Failure:

Harbor is centralized by design. All nodes pull through a single Harbor instance (or load-balanced cluster). If Harbor goes down, image pulls fail. Making Harbor HA means running multiple complex stateful services in HA mode, which takes significant effort.

The architectural question also nagged at me: should I run one Harbor per cluster, or one shared Harbor for both dev and prod? One per cluster duplicates operational overhead. One shared instance couples my environments and requires external networking.

What Harbor Does Well:

If you need Harbor’s features, they’re well-executed:

- The UI is polished and makes management accessible

- Vulnerability scanning with Trivy works well

- If you need a full registry (not just caching), Harbor handles it

- CNCF graduation shows it’s proven at scale

For teams with dedicated ops capacity, Harbor’s capabilities justify the overhead. For a solo operator who just needs caching, it’s too much.

Evaluating Spegel

After Harbor’s complexity, Spegel felt like a breath of fresh air.

Architecture: Distributed P2P Mirror

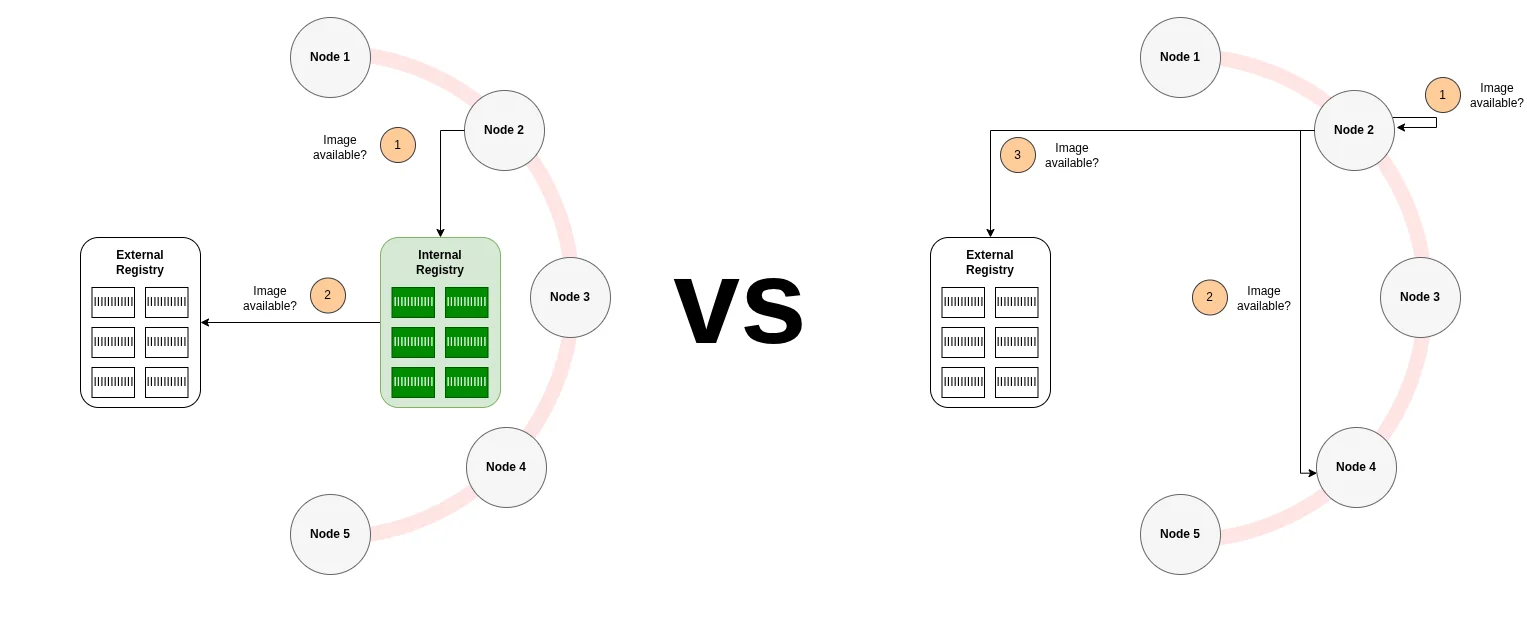

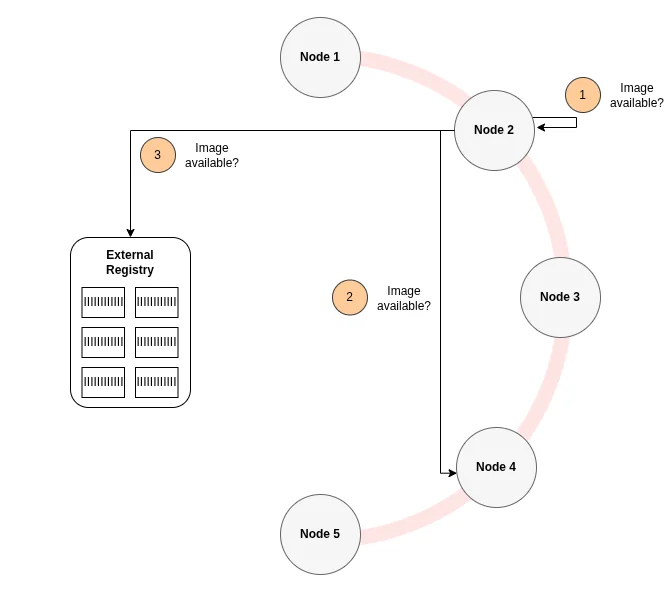

Spegel takes a radically different approach: each Kubernetes node is both a consumer and provider of container images. There’s no central registry, instead nodes share images peer-to-peer.

Core concept:

- Runs as a DaemonSet (one pod per node)

- Each Spegel pod implements an OCI-compliant registry server (HTTP on port 5000 by default via the Kubernetes service)

- Nodes coordinate via a distributed hash table (DHT) based on Kademlia

- Zero external dependencies: no database, no Redis, no persistent volumes

How it works:

-

Image storage: Spegel doesn’t duplicate images. It reads from containerd’s existing content store (

/var/lib/containerd/...) and serves the content via its OCI registry HTTP interface. Images pulled by Kubernetes already exist locally in containerd, Spegel just makes them available to other nodes. -

Discovery: Each Spegel instance advertises which image layers (by digest) it has locally to the DHT, refreshing every 9 minutes and updating reactively when containerd creates, updates, or deletes images. When a node needs a layer, it queries the DHT to find which peers have it.

-

Serving: When containerd on Node A requests an image, it’s configured to check Spegel first (via containerd’s registry mirror config). Spegel on Node A queries the DHT, finds that Node B has the layer, fetches it via HTTP from Node B’s Spegel instance (retrying with alternative peers if Node B fails), and returns it to containerd.

-

Fallback: If no peer has the layer (or peers are unreachable), Spegel returns HTTP 404. Containerd then falls back to pulling from the upstream registry (DockerHub, etc.) as normal.

The key insight:

Spegel doesn’t try to be a registry, it’s a distributed mirror of what’s already on your nodes. By reusing containerd’s storage and implementing a peer-to-peer layer on top, Spegel avoids the complexity of traditional registries. Images are served directly from containerd’s existing content store, which eliminates the operational burden of managing separate state, coordinating cross-node consistency, or implementing backup strategies for cached content.

Operational Reality: The Containerd Config Journey

Setup (the theory):

Make sure those sections are configured in the /etc/containerd/config.toml file on every node and restart containerd after:

[plugins."io.containerd.grpc.v1.cri".registry] config_path = "/etc/containerd/certs.d"[plugins."io.containerd.grpc.v1.cri".containerd] discard_unpacked_layers = falseDeploying Spegel via Helm is trivial:

helm upgrade --create-namespace --namespace spegel --install spegel oci://ghcr.io/spegel-org/helm-charts/spegelDefault configuration worked fine for my experimentation, including the DaemonSet deployment.

Setup (the practice):

Getting Spegel working took about 3 hours, not because of Spegel itself, but because of containerd configuration complexity.

Spegel requires containerd to be configured to use it as a registry mirror. This means modifying /etc/containerd/certs.d/ (or equivalent) on each node. Since I use Ansible for cluster provisioning, I needed to automate this. On the one hand, dealing with toml files was surprisingly annoying with Ansible, but the real issue was containerd.

The containerd config nightmare:

In my case , containerd has conflicting registry configuration sections due to plugin architecture evolution:

-

Legacy CRI v1 section (deprecated):

/etc/containerd/config.toml [plugins."io.containerd.cri.v1.images".registry]config_path = "" # ← Empty value blocks mirror configuration! -

Modern gRPC CRI section (correct):

/etc/containerd/config.toml [plugins."io.containerd.grpc.v1.cri".registry]config_path = "/etc/containerd/certs.d"

I had both sections in my config file. The empty config_path in the legacy section was silently overriding the correct modern section, so containerd never picked up Spegel’s mirror configuration.

The debugging challenge:

Since containerd 2.0, there’s no way to query containerd for its loaded configuration to validate what’s actually active. I had to debug by trial and error: restarting containerd, checking logs, manually testing image pulls. Compounding the issue, images were already present on nodes from prior pulls, so my initial verification steps falsely succeeded (containerd just used the locally cached image, never trying to go through Spegel).

The solution: Configure both sections, the outdated and the current one, accordingly. Once this was sorted, Spegel worked flawlessly.

Day-to-day operations:

Since deployment, Spegel has required zero maintenance interventions. The absence of external dependencies (databases, certificate infrastructure, persistent volumes) means there are no routine operational tasks beyond standard Kubernetes workload monitoring.

Failure modes:

What could go wrong?

- Containerd config drift: If I change containerd configuration during upgrades, I might break the mirror config. This is the main operational risk. Same goes when upgrading Spegel, should it ever require more changes to the containerd config.

- Node churn: When a node goes down, its layers remain advertised in the DHT briefly (TTL is 10 minutes, with advertisements refreshed every 9 minutes). This adds slight latency to pulls (DHT query timeouts) but Spegel falls back to upstream registries immediately.

- Spegel pod crashes: If Spegel crashes on a node, that node simply pulls from upstream or other peers. There is no cluster-wide impact.

The failure consequences are minimal since Spegel is designed as purely an optimization layer. If it fails, the cluster continues working normally, just pulling from upstream registries.

Resource requirements:

- CPU/Memory: Negligible since Spegel is idle until an image pull happens

- Storage: Zero additional storage because it reuses containerd’s content store

- Network: Spegel adds inter-node traffic for image distribution, but reduces external bandwidth in turn

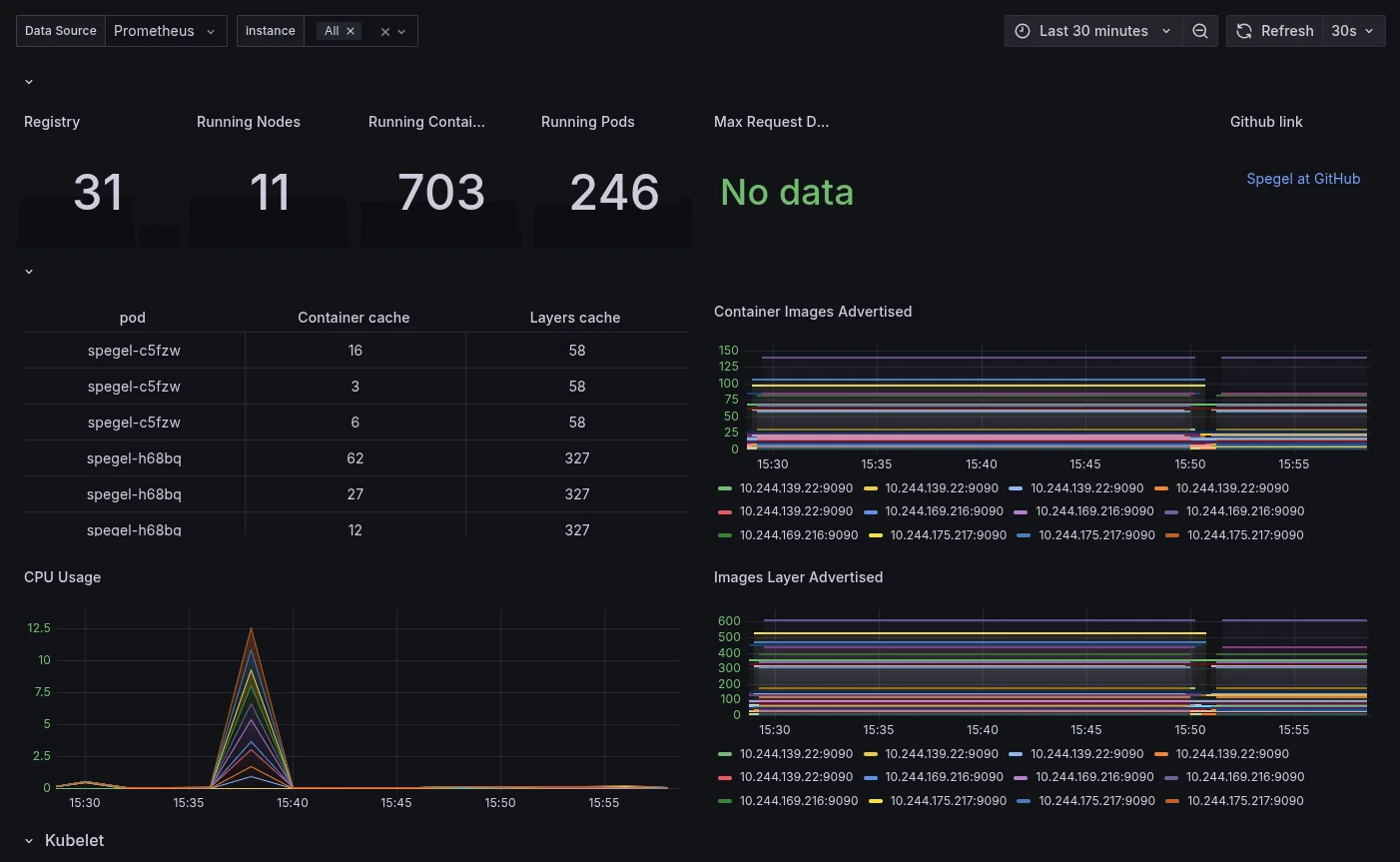

Monitoring with Prometheus and Grafana:

Spegel comes with built-in Prometheus metrics and can automatically provision a Grafana dashboard. Here’s the configuration I used in my Helm values:

# https://github.com/spegel-org/spegel/tree/main/charts/spegel# https://github.com/spegel-org/spegel/blob/main/charts/spegel/values.yaml

spegel: serviceMonitor: enabled: true

# This configuration assumes that Grafana's sidecar is configured to watch ALL namespaces. # In the Grafana Helm values, ensure: sidecar.dashboards.searchNamespace = "ALL" grafanaDashboard: enabled: true labels: grafana_dashboard: '1'This automatically creates a ServiceMonitor for Prometheus to scrape Spegel metrics, and provisions a Grafana dashboard that shows key operational metrics like the container images and image layers that are advertised.

How Spegel Matched My Criteria

Kubernetes-Native Integration:

Spegel is genuinely Kubernetes-native:

- Deployed as a standard DaemonSet using Helm

- Uses Kubernetes service discovery (other nodes reach Spegel via

spegel.spegel.svc.cluster.local) - Integrates with containerd’s native registry mirror configuration

- Prometheus metrics via ServiceMonitor (standard K8s monitoring pattern)

Operational Complexity:

After initial containerd configuration, Spegel requires minimal ongoing operations:

- Stateless architecture: Reuses containerd’s storage, eliminating database backups, replication management, and storage coordination tasks

- Internal HTTP-only: Operates within the cluster boundary, avoiding certificate issuance, distribution, and rotation overhead

- DHT-based peer discovery: Relies on ephemeral distributed hash table state rather than persistent configuration files requiring synchronization

- Standard monitoring: Integrates with existing Prometheus/Grafana infrastructure via ServiceMonitors

- Rolling updates: Helm chart upgrades follow standard DaemonSet update patterns

- Primary operational risk: Maintaining containerd configuration consistency across node upgrades and Spegel version changes

Single Point of Failure:

Spegel is architecturally distributed. Every node is both client and server. If three nodes have an image layer and one goes down, the other two continue serving it. There’s no central registry to fail.

The DHT provides peer discovery with minimal coordination overhead. While leader election occurs for some operations, the short 10-second lease times ensure rapid failover when nodes become unavailable.

What Spegel Doesn’t Offer:

Spegel is deliberately focused on distributed image mirroring. Features outside this scope include:

- Vulnerability scanning

- Image signing or content trust

- Web UI for management

- Multi-tenancy or RBAC

- Metrics about which images are cached (though it provides operational metrics about layer distribution)

- Push capabilities (mirror-only, not a full registry)

For my use case (pure pull-through caching) these omissions don’t matter.

The Decision

Against my three criteria (Kubernetes-native integration, minimal operational complexity, and no single point of failure) Spegel was the clear winner.

Harbor’s feature set is impressive, but my use case didn’t need vulnerability scanning, multi-tenancy, image signing, or a full registry platform. What I needed was simple: stop hitting DockerHub rate limits when provisioning nodes.

Spegel solves exactly that problem with minimal complexity: a DaemonSet that reuses containerd’s storage, peer-to-peer image distribution, and graceful fallback to upstream registries. The architecture eliminates the need for databases, certificate infrastructure, and architectural decisions about in-cluster vs. shared infrastructure placement.

For projects with limited operational capacity, the reduction in operational complexity outweighs the value of unused features.

When to Choose Which

Your context is different from mine. Here’s how to decide:

Choose Spegel if:

- You need pull-through caching to avoid rate limits

- You’re operating solo or with a small team

- You want minimal operational complexity

- You value distributed architecture without single points of failure

Choose Harbor if:

- You need a full registry for hosting private images

- You have dedicated ops capacity for stateful services

- Vulnerability scanning, RBAC, or compliance features are requirements

- Multiple teams need a shared registry platform

Key Lessons

1. Kubernetes-Native means more than “runs on Kubernetes”

Harbor deploys on K8s but feels like traditional infrastructure ported over: databases, certificates, centralized state. Particularly, the configuration-as-code functionality is missing. Spegel embraces Kubernetes primitives: DaemonSets, Services, containerd integration. For operational complexity, this distinction matters.

2. Unused features incur operational costs

Every feature in a system has operational costs: infrastructure to maintain, failure modes to understand, upgrade paths to test. When evaluating tools, consider not just what they can do, but what maintaining those capabilities will cost your team in ongoing operational overhead.

3. Evaluate by deploying, not just reading

Documentation made Harbor seem reasonable. Deployment revealed friction: certificate management, proxy project configuration, HA complexity. The containerd config issues with Spegel similarly only surfaced hands-on. Test in practice before committing.

Conclusion

The choice isn’t about “which is better” but which better fits your constraints.

For my project (two bare-metal clusters, solo operator, DockerHub rate limits) Spegel’s simplicity won. Harbor’s features would have been overhead without corresponding value.

Choose the simplest solution that solves your problem. Upgrade only when complexity is justified by real necessity.

The lack of required maintenance interventions since deployment validates the choice. Infrastructure requiring minimal operational attention is infrastructure designed appropriately for its context.

Resources:

- Spegel GitHub: https://github.com/spegel-org/spegel

- Spegel Documentation: https://spegel.dev/docs/

- Harbor GitHub: https://github.com/goharbor/harbor

- Harbor Documentation: https://goharbor.io/docs/

This article documents a real infrastructure decision made while building a Kubernetes-based platform, analyzing the architectural and operational trade-offs between centralized and distributed approaches to container image distribution.